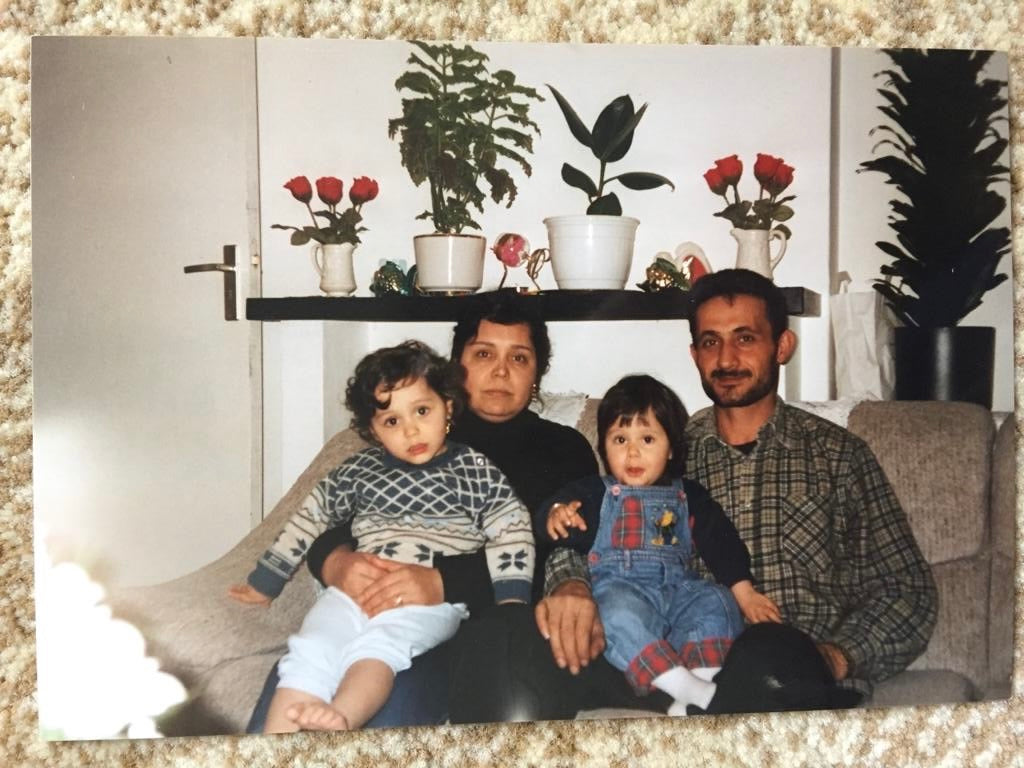

Let’s begin at the beginning. Thirty years ago, my parents fled Syria. For legal reasons, I can’t go into every detail. Let’s just say… communism. (I’m joking, of course.) The truth is, my parents knew there was no future for Kurds in Syria, and so they decided that Europe would be their best chance.

Until 2010, we lived in the Netherlands without papers, which meant we couldn’t visit our family in Afrin. And after 2010, well… the brutal war made it impossible anyway.

Then came December 2024. A militia overthrew Bashar al-Assad, and slowly, the borders began to reopen. For us, that was the sign: this was the moment. My mother could finally see her father again after thirty long years. And for me, it was the chance to meet my grandfather for the very first time.

The moment I booked the tickets (three months before our departure) my mother came alive in a way I hadn’t seen for years. She spent her days dreaming about what to pack: tools, clothes, and of course, stroopwafels. She had her spark back.

Me? I wasn’t sure what to expect. A broken country? Family I barely knew? Like many children of migrants, my only “conversations” with them had been short, slightly awkward holiday calls: being pushed toward the phone on Eid al-Fitr to say Eid Mubarak to relatives I’d never met. I worried about what I’d even talk about once we were there. My Kurdish is fine for small talk, but when it comes to explaining what I study… forget it. I’d be stuttering, dropping Dutch words in between, and glancing at my mom to rescue me.

Before we left, my mother reminded my sister and me how we were expected to behave. “Remember, Syria isn’t like the Netherlands,” she said. “You can’t say to someone that they ‘don’t understand.’ You can’t just walk down the street in short sleeves. And you always, always have to obey the elders, no matter what.”

We promised to behave, and maybe we even meant it at first. But in the end, our personalities were too strong. We ‘misbehaved’ by Syrian standards, though always unintentionally. Thankfully, instead of taking offense, everyone laughed at us. If anything, I like to think we brought a little cultural shift with us. Who knows?

At the border, we were scrutinized carefully: who were these visa-less Dutch people? Luckily, my mother had been prepared for years: she had registered us in the family record long ago. A few stamps later, we were through.

The moment my mother saw her father, she collapsed into tears, kissing his hands, his feet, his head. My sister Zainab and I followed, kissing his hands in turn. Zainab, braver than me, kissed his feet too (which made everyone laugh later). I wanted to cry, but I didn’t. I was surrounded by strangers, even if they were family.

We piled into a huge Hyundai pickup, our suitcases stacked high. I chose to ride in the back, among the luggage, because I wanted to take it all in: to smell the ride from Aleppo to Afrin, to see it with my own eyes. And I’ll be honest: Syria doesn’t smell good. Exhaust fumes, burnt plastic, dry heat… it’s overwhelming.

When we finally arrived at my aunt’s village near Afrin, where my grandfather now lives with her, a sheep was immediately slaughtered. My grandfather had always promised he would do this to celebrate our safe arrival. And he did. I’ll spare the details, but it was done humanely, and the animal didn’t suffer.

Upon arrival, Zainab discovers that pomegranates grow in my aunt's garden.

A picture of the son of my cousin, my aunt, my grandfather, Zainab and my mother.

We wandered into one of the olive groves that has been in our family for generations. It was there, among the trees, that I had my first real conversation with my grandfather. He spoke about the importance of knowing which trees are ours, and of keeping the land in the family. These fields have been his life’s work, tended by his hands for as long as he can remember - so that we, his children and grandchildren, might one day share in their harvest.

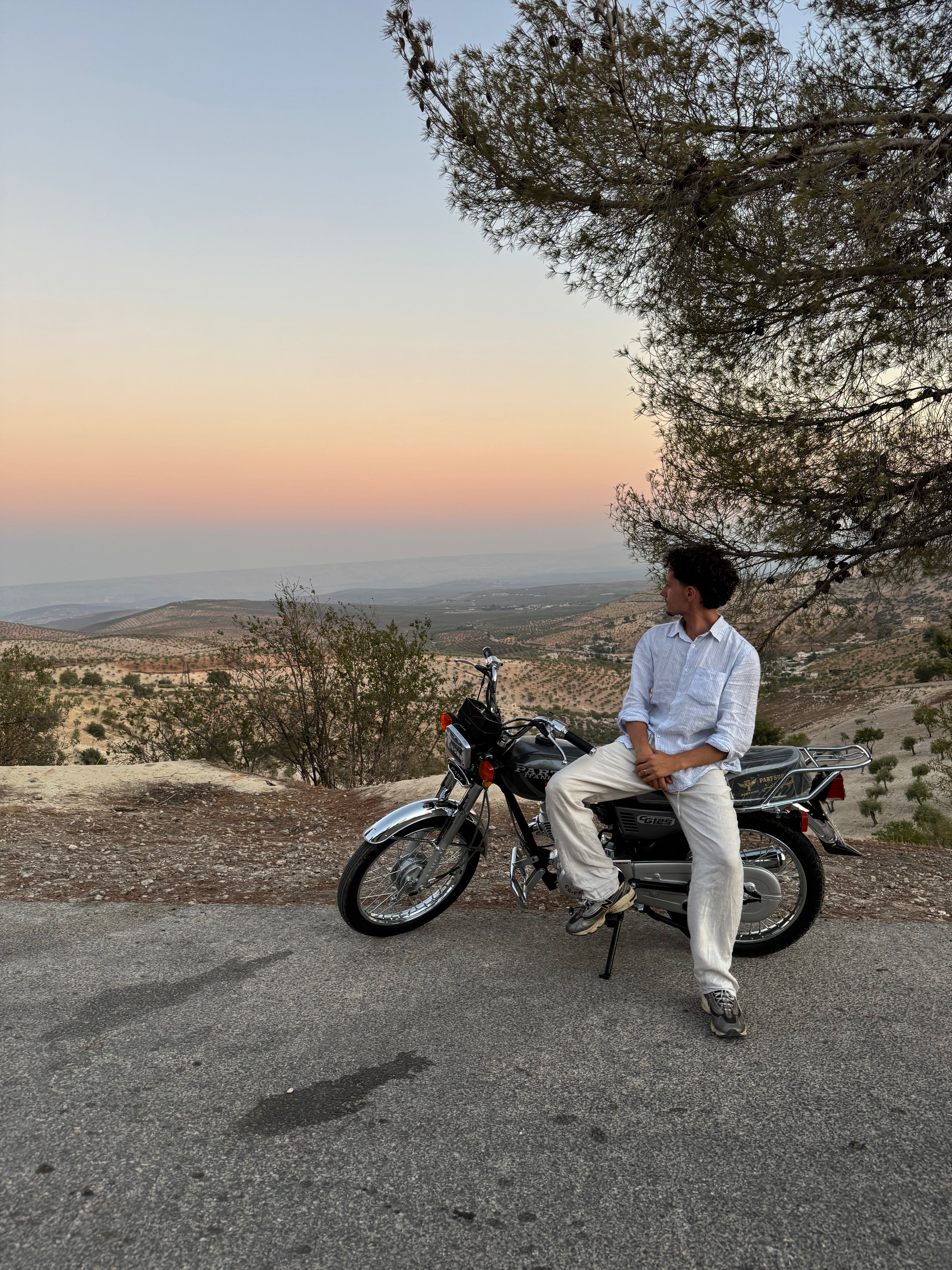

My father always said that the first thing he would do when he returned to Syria would be to ride his motorcycle. By Dutch standards, this is a very simple 125cc motorcycle. But every Syrian or Kurd knows these motorcycles, a motorcycle that sometimes carries families of six, a motorcycle that you ride without a helmet, without protection. And of course, I had to do that too. We drove to Kafr Dalī at Taḩtānī. The view was incredible.

In the evenings, the house comes alive. Guests arrive, baklava is served in generous portions, and the air fills with the aroma of coffee, tea, and sweet smoke from the hookah. Young and old gather together, sitting side by side on cushions spread across the freshly swept courtyard. The daytime heat makes it nearly impossible to spend time outside, but when night falls, the air cools and the best conversations unfold. This is when laughter lingers, stories are shared, and the true heart of the day begins.

As I mentioned earlier, I met all of the family members you see here for the first time in Syria. This man, my uncle, my father's brother, is no exception. He enjoys hunting and, like most Syrians, smokes a lot of cigarettes. His wife and children had gone to see the doctor in Aleppo (about an hour's drive away). We hadn't been sitting there for five minutes when he immediately asked my sister (whom he was also meeting for the first time) if she could make us some coffee. My aunt, mother, cousin, and I had to laugh out loud, because where in the Netherlands would anyone ever ask their visitors if they could make coffee? In Syria, it seems to be normal.

My uncle and grandfather are picking figs here. For your information, these figs are not purple, they are yellow/greenish, and they are the most delicious figs you could ever eat. I still think about them every day. They were like honey candies. I miss them.

Since my paternal grandparents had passed away, we also intended to visit their graves. It was emotional, even though I must admit that I did not know them. Nevertheless, it felt important to commemorate them, if not for myself, then for my father. My grandfather sought some shade and, as depicted on the olive oil bottle, he sat in the shade in this manner.

I don't think there's much to say about this photo. However, we noticed that there are few texts, slogans, or art written on the walls. Perhaps there used to be, but everything has been removed. This was the only cry for attention I saw in Syria.

My uncle, Muafak, drove a taxi with his son. To me and my sister, he became more than an uncle: he became a symbol of resilience. He had already endured more suffering than most can imagine: the long years of war in Syria, and the unbearable loss of his daughter.

During the war, they lived in Aleppo, among the Kurds. One cold February day, his little girl, just six years old, was walking outside with her four-year-old brother. From a distance gunmen opened fire. A single bullet struck her in the side. She collapsed to the ground.

The family watched in horror, frozen. They couldn’t reach her. Anyone who stepped into the shooter’s line of sight risked being gunned down as well. It was only when a brave neighbor ran forward, risking his own life, that her body was carried away. They rushed her to the hospital, clinging to hope. But it was too late. My little cousin, Jacqueline, was gone. Murdered by cowards with guns, in a war that brought nothing but devastation.

My uncle’s children told me how they lived on the edge of survival. They often went without food, but sometimes Kurdish neighbors would slip them potatoes or rice in secret. Fourteen years of fear marked their childhood. Years no child should ever endure. And though they survived, they carry scars that will never fully heal.

The views from a mountaintop in Afrin

In Syria, everyone drives a tractor. My father told me I had to learn to drive a tractor so that I could work in the olive fields later on. No sooner said than done. I learned how to drive between the olive trees. In my Arab robe at sunset.

Backgammon is a game I’ve played for years with my friends and my father. My cousin knew how to play too, but he didn’t have a board. Of course, we had to change that. So, after a five-hour drive to Damascus (and five hours back) we finally found a beautiful one. The pieces turned out to be a little too big, but we solved that later by buying new ones. And as for the games we played… I’ll stay humble, but somehow, I always ended up winning.

As if the war hadn’t already left enough scars, recent earthquakes in Turkey and Syria shattered what little remained. Among the ruins was the house where my mother was born. It felt almost impossible to believe that she had once lived and grown up in what is now nothing more than a pile of rubble. Confronting her childhood home in this state left a deep mark on her.

This is Mustafa. He once served in the army and still works under the current government. Eight years ago, he decided to leave the city of Aleppo behind and move to the villages. That’s where he met my grandfather, who offered him shelter in exchange for helping on our land, along with a small wage.

When I arrived, Mustafa was excited to finally meet “the owner” of the olive fields. I had to laugh at that; I would never call myself the owner. His tools, however, told their own story: old, blunt, and worn down, because his good ones had been stolen. Luckily, my mother had come prepared. Among the 80 kilos of supplies she brought, there were brand new tools, ready to put to use.

I haven’t spoken much about this uncle, Abdelkader. He had no teeth, which gave him a childlike appearance, but behind that smile was a story of deep suffering. One year ago, the government arrested him, accusing him of belonging to a terrorist organization. In prison, he was beaten, humiliated, and tortured to confess to something he had never done. There was nothing to confess. It took ten thousand dollars for the family to secure his release. As if surviving a war wasn’t enough, he also had to survive this trauma.

This photo was taken at the very end of our trip. Amm (read: uncle) Abdelkader insisted on having his picture taken with me, because, secretly, he liked me. A loudmouth nephew who could laugh at himself and take a joke.

Almost everyone came to the airport to see us off. Everyone except my aunt, and my cousin’s wife and son (she was heavily pregnant and couldn’t come). My aunt had to stay behind because, for some reason, a guest had decided it was a good idea to visit the night before and linger into the morning. But I won’t waste any more words on her.

Just as we were leaving, my aunt suddenly ran after us, waving goodbye as Zainab and I sat in the back of the pickup truck. We waved back, and the moment I stopped filming, tears started streaming down my face. Zainab put her arm around me and whispered, “But we’ll be back?”

Of course we’ll come back. Someday. But still, that farewell cut deep, and it still does. My aunt had spent ten days working tirelessly to make sure we had a beautiful trip. Thank you, Xoltik Khadija, you gave us everything, and for that I will be forever grateful.

At the airport, everyone was in tears. Not only Amm Abdelkader, Bave Mannan (my grandfather), my cousin Chilou (whose name means “blondie” in Kurdish), Zainab, my mother, and me. But also, to my surprise, my uncle Muafak, his wife, and their children. The farewell was heavy, almost unbearable.

My mother stayed behind and will remain in Afrin for a few more weeks. But I think Zainab and I have left our mark. Two Europeans, two Dutch children of exiles, stepping for the first time onto Syrian soil. We carried with us the Kurdish we had learned at home, imperfect but alive, and brought a playfulness that met the sorrow of a devastated land.

We laughed. We played. We hugged. We cried. We even got sick — ten days of diarrhea (note to self: don’t drink the water) — but still, each day we tried to embrace Syria with open hearts. Afrin, Rojava. Family, friends, and above all, our grandfather.

And perhaps most moving of all: the people who had once been strangers to me, faces I had only heard about in stories, voices I had only known through holiday phone calls, became something more. In those short days, they became my family. My home. My roots made flesh.

I am endlessly grateful for this journey, for the chance to connect with a place I had only ever imagined. And I carry one hope with me still: that one day, I will return, this time with my father by my side.